Three months since an outbreak of avian influenza in U.S. dairy cattle was declared, the country is failing to take the necessary steps to get in front of the virus and possibly contain its spread among cows, according to interviews with more than a dozen experts and current and former government officials.

The country still does not have a sufficient testing infrastructure in place, nor a full understanding of how the virus is moving within herds and to new herds, experts say. Government officials also have not secured the cooperation from farmers and dairy workers that would be required to rein in the outbreak.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has stated that its goal is to eliminate the virus, known as H5N1, from cattle. But that messaging has left scientists scratching their heads about how exactly officials plan to stop further transmission given that the impediments persist. It’s also not clear whether the virus could burn out, or if cows are vulnerable to reinfection.

“If that was the goal, we should have been doing a lot of other things from the beginning,” said Seema Lakdawala, an influenza expert at Emory University. “We could have been working toward that for the last three months, rather than trying to play catch-up now.”

Other countries are taking notice. Last month, a committee of scientific advisers alerted the French government to the “unprecedented situation” happening 4,000 miles away, saying that while the start of the virus’s spread among cows had not yet increased the threat to people, it was concerning enough that the government needed to take its own measures.

“The situation is serious,” Bruno Lina, a virologist and member of the committee, told STAT, noting that European countries were already expanding their surveillance systems to include cows. “It has to be taken seriously in the U.S., and that is what we expect from the U.S.”

But by just about all accounts, not enough is being done.

USDA maintained that its scientists, veterinarians, and animal health experts “have been working at all hours, day in and day out” to respond to the virus. The agency also said as it continues to increase outreach to raise awareness of the programs USDA has started, the agency expects testing to increase in the weeks ahead.

“The actions we have taken to limit movements, improve biosecurity and encourage testing are expected to establish the foundation for eliminating this virus from the dairy herd,” the agency said in a written statement provided to STAT.

The USDA said the agency is “taking animal health and human health concerns seriously through a whole-of-government response.”

Agency officials first announced the virus had infected dairy herds on March 25, though it’s perhaps been seven months since the outbreak actually started.

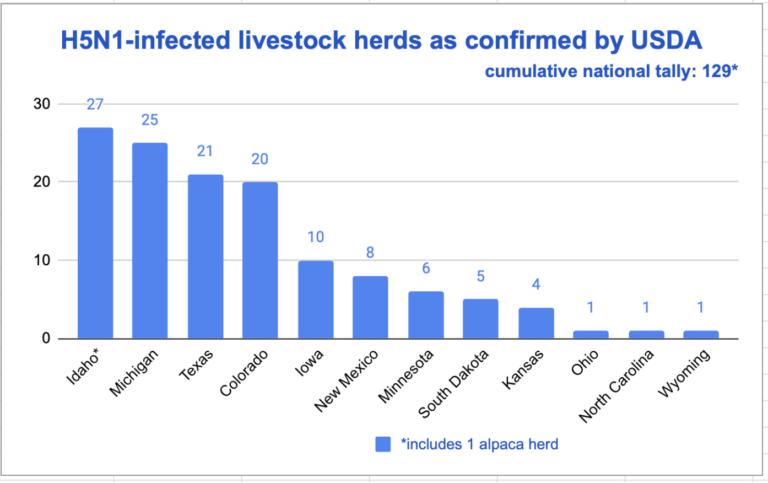

To gauge the risk of the situation and assess the response, STAT spoke with a range of experts both in the U.S. and internationally. What emerges is a portrait of a threat that is steadily rolling along, yet also settling into what feels like a routine. Nearly every day, a few new herds are found to have infections, entrenching the virus deeper into the cattle population and expanding its footprint across more states. As of Wednesday, 129 herds in 12 states have reported infections, although those figures are widely assumed to be underestimates because many farmers are refusing to test. Three farmworkers, in Texas and Michigan, are known to have developed mild cases of H5N1, presumably from close contact with cows.

But if the dynamics of the outbreak haven’t changed, neither, experts say, has the forcefulness of the response.

While the situation presents both scientific and logistical challenges, a chief concern is that neither the government nor outside scientists know just how far and wide the virus has spread because critical data have either not been collected or transparently relayed. The government still does not have an adequate surveillance system in place to keep up with the outbreak, scientists say.

Agricultural authorities are still releasing only partial data from the genetic sequences of the viruses they’ve sampled. There is not widespread testing of cows or of workers on dairy farms, leading to fears of missed infections, both bovine and human. Broad serology studies of either cows or people — which could detect antibodies to H5N1 in blood and provide an estimate of the true scope of infections — have yet to release results, though at least one is underway in Michigan.

These are all complaints that experts have been lodging for weeks, if not longer. The failure to address them, they say, is hamstringing efforts to track the virus, to contain its spread in cattle, and to see if it’s adapting in ways that could make it more likely to jump to people.

“If you still can’t determine the scale of the outbreak, and which states, what farms, what herds, are actually being affected, I don’t see how you can possibly think that it’s containable,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan.

USDA said that the agency provided sequencing data immediately to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and has made information publicly available. The agency also said it has sent epidemiological strike teams to Michigan and Iowa at the states’ requests.

Even if the outbreak seems to be following a pattern, that might not always be the case. Scientists note that H5N1 bird flu has forced regular rewrites to flu dogma since it emerged as a risk to people nearly three decades ago.

“It doesn’t appear that the overall animal outbreak is changing in character, as of yet, but it’s difficult to know because we have so little data,” said Tom Inglesby, the director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, who, like several experts, argued that if this outbreak were playing out in another country, U.S. officials would be calling the response unacceptable.

Limited measures, reluctant farmers

Over the past few months, authorities have rolled out a number of interventions, trying, for example, to bolster protections for dairy workers and incentivize farms to expand surveillance. They’ve put up some money for farms to improve biosecurity measures and widen testing, though only a fraction of farms, including those with infected herds, have taken the government up on its offer. States are trying to give away personal protective equipment that could be worn in milking parlors, but again, few farms have expressed interest. Within a month of the identification of the outbreak, federal authorities started requiring testing of lactating dairy cows, though only when they crossed state lines, and even then, only a limited number per shipment, chosen by the farmer.

Agencies are trying to widen their approach. The CDC has started publicly tracking influenza A viruses — the family to which H5N1 belongs — in wastewater samples. And states are taking their own steps beyond quarantining infected herds. In Iowa, for example, agricultural authorities have started requiring testing of dairy cows around infected poultry flocks. Several states are requiring lactating cows to be tested for flu before they can be brought to fairs.

But the government’s own data indicate the efforts have holes large enough for the virus to run through. In one USDA survey, 60% of farms acknowledged moving cows within a state even after the animals had started showing symptoms of infection. Federal officials have acknowledged they’re not getting much cooperation from dairy producers and workers.

“The more we learn about H5N1, the more we understand that good biosecurity is a critically important path to containing the virus,” Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack wrote last week in an op-ed in the media outlet Agri-Pulse, calling on farmers to step up the use of PPE, limit traffic onto their farms, and increase cleaning and disinfection practices in their barns and milking parlors.

“It’s not [being] managed as a zoonotic disease that is a potential dynamic threat. It may well not become a pandemic. But I think it’s playing with fire.”

Marion Koopmans, chief of viroscience at Erasmus Medical Center

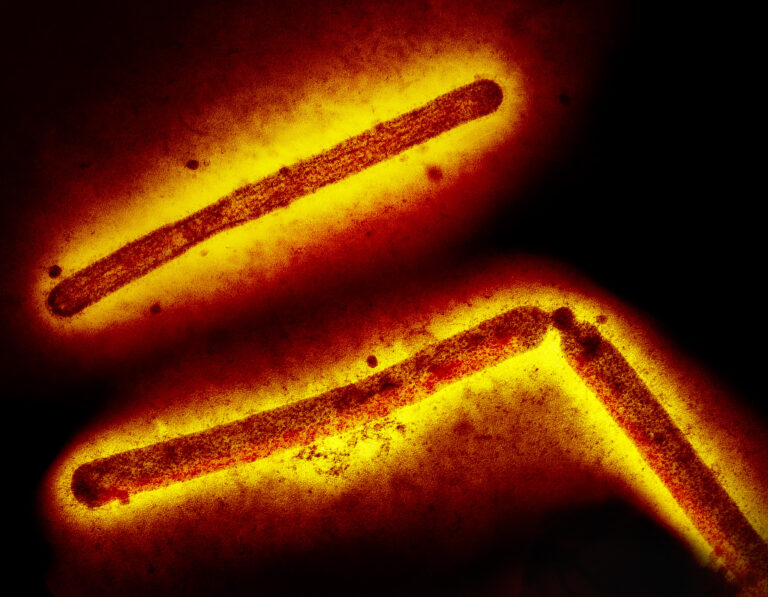

H5N1 has been on scientists’ radars as a threat since the late 1990s, and over the years, it has managed to spill from wild birds into different mammalian species, causing infections that seemed more like one-offs. But an H5N1 strain that emerged a few years ago seemed to change the game. It has been carried by migratory birds to just about every corner of the world, decimating poultry flocks along the way and infecting more and more mammals. This version of the virus is the one that is transmitting among dairy cows.

The ongoing spread among cows raises particular concerns, not limited to the economic toll the virus could take on farmers by depleting cows’ milk or by preventing them from selling product. As the virus has spread, so too have fears that it could become an endemic pathogen in a species that has considerable contact with people, creating a lasting risk to dairy workers. Underlying it all is the grave concern that the virus could one day evolve in ways that make it better at spreading to and among people.

The virus is not there yet, and scientists say it would likely need to change in a number of ways for that to happen. But they believe the nature of the current spread could conceivably lay the groundwork for the next pandemic. Historically, the virus has had an alarmingly high fatality rate when it has caused human infections, though all three documented human cases that have emerged from the cattle outbreak have been mild.

“It’s not [being] managed as a zoonotic disease that is a potential dynamic threat,” said Marion Koopmans, chief of viroscience at Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands. “It may well not become a pandemic. But I think it’s playing with fire.”

Familiar hurdles

In some ways, experts say, the bird flu outbreak is exposing the same systemic obstacles that hobbled the U.S. performance during the Covid-19 pandemic. The response is falling on various local, state, and federal agencies with limited authorities and disparate, sometimes competing, agendas. In this case, it’s a balkanization compounded by the need for public health officials to collaborate with agricultural agencies, which are often tilted to supporting industry instead of prioritizing reining in threats to human health. State agricultural agencies are also underfunded and understaffed; meanwhile, some portion of the public is resistant to measures to track and control the virus.

“There seems to be a lot of issues between the agencies, the federal government, the states, the farmers,” said Florian Krammer, a flu virologist at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine in New York. “It’s not looking like everybody’s on the same side trying to get rid of the problem.”

Many scientists acknowledge the tightrope that government officials are treading. Fearful of overstepping, agencies are reluctant to use the full extent of their legal authority to demand testing on farms — something that could lead to a political backlash in an election year. Such a response would be perhaps all the more likely in a post-Covid pandemic world, and would impede whatever receptiveness farmers are showing.

Beyond the mistrust of government agencies some farmers harbor, dairy producers, working with slim margins to begin with, have real economic concerns. If they report an infected herd, they can’t sell milk or move cattle, which are frequently transported for breeding and grazing. Veterinarians who have been working with farmers told STAT that while some infected herds have been cleared to return to milk production, farmers still fear what a positive test means for them. Given the risks, it’s easier not to test.

“Even though I’m disappointed by some of the things the federal government is doing, I understand the constraints they’re working under,” said Andrew Pavia, the chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Utah, who also works on public health preparedness. “And even though I’m disappointed by some of the barriers that farm associations and farmers are throwing up, I understand where they’re coming from. I think we need to work together to figure it out.”

Thorny challenges stand in the way of looking for human cases as well. Private farms might not give public health agencies access, and even if they do, dairy workers might dodge testing. A positive test could mean missing work and lost income. Many farmworkers do not speak English, and may not have health insurance. A portion are presumed to be in the country illegally, aspects that discourage cooperation with health investigations.

Public health officials have made clear they’ve run into these problems. A study of the first human case tied to the outbreak — a Texas dairy worker who developed conjunctivitis — reported that the man and his contacts refused to have their blood drawn for serology tests, which could have shown whether others were infected.

As of mid-June, just over 50 people had been tested for novel influenza strains, which would include H5N1, according to the CDC’s most recent figures.

“Do they get time off when they’re sick? If not, will they be willing to come forward to declare themselves feeling ill?” Laszlo Madaras, the chief medical officer of the Migrant Clinicians Network, said during a webinar last week for rural providers, whom he stressed could be trusted sources of information for dairy workers.

Possible ways forward

Such dynamics give rise to the question of what an effective response should look like — one that coaxes greater participation from farms, improves surveillance, and fits with what agencies are empowered to do.

Several experts said state and federal agencies, as well as rural doctors and veterinarians, need to conduct education campaigns, both to outline steps that dairy workers can take to prevent infections, and to explain to farmers how being transparent can help protect herds and the safety of the milk supply. Whatever steps are being proposed, they said, producers have to get on board if they’re to succeed.

“Unless you’ve got 80% of the industry in a position to support you, you don’t have the manpower, or the dollars, to dictate what you’re going to do,” said John Korslund, who worked as a USDA veterinarian for two decades. “So it’s very much a cooperative effort. And if you’re not in a position where you can get cooperation from the industry with what you’re proposing to do, you can’t do it.”

USDA said the agency is working with the food and agriculture sector and “hand in glove” with state health officials to raise awareness about available resources. The agency has been hosting regular meetings to share updates and hear concerns, a spokesperson said.

The trust gap with farmers has continued even though some federal officials are well-connected to the dairy industry. Vilsack, for example, used to be a top-paid executive at Dairy Management, a trade association that promotes milk and dairy products.

“He’s shown time and again that he’s on the side of farmers, and, you know, particularly dairy farmers, right?” said Brian Ronholm, Consumer Reports’ director of food policy and a former USDA food safety official. “So if anyone can kind of reach that divide, it is someone like him.”

Other ideas that experts called for included bulk testing of milk, which could narrow geographically where new outbreaks are occurring. So far, that is only being done voluntarily, by a tiny number of farms. Many said there needs to be testing of asymptomatic cows, as well as those showing signs of illness. Some scientists are arguing for vaccinating cows, though that is still a point of debate.

A USDA spokesperson said that the bulk milk testing is in its “initial pilot phase” and that six states are enrolled as of Tuesday: Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, Texas, Ohio, and North Carolina. The agency is conducting outreach to provide more information about the program, the spokesperson said.

Some experts pointed to measures other countries are taking — even though no other country has documented a cattle infection — as steps that could help the U.S. get ahead of the virus.

“There seems to be a lot of issues between the agencies, the federal government, the states, the farmers. It’s not looking like everybody’s on the same side trying to get rid of the problem.”

Florian Krammer, flu virologist

Thijs Kuiken, a pathologist at Erasmus Medical Center, noted that Canada has made it mandatory to report suspected H5N1 cases in cows; in the U.S., only positive tests have to be reported to federal authorities. (Some states have also said suspected cases need to be reported.) Researchers in Germany have made public early results from serology studies in cows.

It’s also a matter of money, many experts said. The government might simply need to pony up more resources both as a way to get access to farms for testing and to cover farmers’ losses if they have an infected herd and can’t sell milk. Experts noted that the government pays poultry farmers for birds that need to be culled to contain H5N1 outbreaks in domestic flocks.

A program to cover some portion of lost milk production has been announced, but authorities are still ironing out the details. The program will be retroactive to the date herds were confirmed positive, the USDA said.

“USDA anticipates that its forthcoming rule will specify that farmers will receive payments at 90 percent of lost production per cow,” an agency spokesperson said.

Ultimately, though, there are constraints on the incentives agencies can offer. The Biden administration isn’t likely to get any additional funding from a Congress split between Democrats and Republicans. Multiple senators said in brief interviews with STAT that administration officials haven’t asked for more resources.

John Auerbach, a former CDC official during the Obama and Biden administrations who is now a public health consultant at the firm ICF, said the administration’s reticence to ask for more money is not surprising, given the difficulty that Congress has had simply keeping the government open.

“I understand why the Democrats would be reluctant to open that can of worms up again,” Auerbach said.

The USDA reiterated that the agency has approved a transfer of $824 million from a separate funding stream to support response efforts. The secretary of agriculture can authorize additional funding to address emergency outbreaks, like a previous $1.3 billion tranche approved to increase detection of avian influenza in wild birds and poultry.

A unified approach

Fundamentally, experts said, the U.S. needs a more coordinated response instead of the piecemeal approach it’s seen so far.

“It only takes one state to be doing a really bad job or to be covering up or something for it to then be getting into further states, and the outbreak carries on,” said Thomas Peacock, an influenza virologist at the Pirbright Institute, a British organization that focuses on controlling viral illnesses in animals.

For all the political and economic challenges, scientists have plenty of questions to answer as well.

For one, there is still not a comprehensive understanding of the way, or ways, the virus is spreading. The repeated use of milking equipment from cow to cow seems to be a key route, but scientists think there have to be other, undiscovered viral pathways that haven’t been specified beyond the movement of equipment, cows, and people from farm to farm.

The scientific specifics of this outbreak are also complicating the response. Many of the world’s top flu scientists have acknowledged they didn’t think cows could get H5N1, a blind spot that delayed pinpointing the virus as the culprit behind a decline in milk production among cows in the Texas Panhandle. And while other mammals, with a few exceptions, haven’t spread H5N1 to others of their species, it seems the virus is moving quite efficiently from cow to cow, though likely with human help, via milking equipment.

The challenges go on. Cows, generally, aren’t getting that sick. The three related human cases have all been mild. It’s easy for those types of incidents to be ignored or missed, giving the virus a chance to spread silently.

Scientists credited the government with policy changes that haven’t earned many headlines but that they say are helpful. A tweak in how the USDA classifies H5N1 has allowed additional researchers to study the virus, Emory’s Lakdawala said. (They still need a USDA permit and must conduct the work in a high-containment lab.) More scientists are now trying to crack open some of the basics of the virus — how it spreads, how it’s evolving, the quality and durability of immunity — and it’s made it more feasible to do wastewater monitoring for the virus.

The CDC is also flagging to health care providers the possibility of human cases. The agency has encouraged clinicians to test people for flu even though in the summer the usual human flu strains transmit at very low levels.

“It’s really important when you’re seeing a patient that might have acute respiratory illness or conjunctivitis, whether or not they have a fever, even if they appear to have clinically mild illness, you should ask them what they do,” Tim Uyeki, the chief medical officer of the CDC’s influenza division, said on the webinar for rural clinicians. “What kind of work do they do? Do they have potential occupational exposure to an infected animal?”

To some scientists, the situation on dairy farms is not some new threat, but rather an extension of one that’s been building as H5N1 has swept around the world. While the outbreak stoked particular concerns — such as cows’ close contact with people, and the risk to the milk supply — they argued that the latest event has only highlighted how important it is for the world to give more attention to the virus broadly.

“Arguably, the global spread of this virus over the last four years — the fact that it has been jumping from species to species quite happily — to me, that already felt like a big enough call to arms,” said Colin Russell, an evolutionary biologist at Amsterdam University Medical Center and chair of a European network of influenza experts. “We have to be very careful in the presentation of this, not as, ‘Oh it’s in cattle, now there’s going to be a pandemic,’ but more that this is just a further illustration of the potential of this virus and the fact that we need to be taking the whole H5 situation seriously, globally,” he said.

Eric Boodman contributed reporting.

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.

STAT encourages you to share your voice. We welcome your commentary, criticism, and expertise on our subscriber-only platform, STAT+ Connect