LONDON — Finland is preparing to offer vaccines to people at risk of exposure to an avian influenza strain spreading among farmed and wild animals, health officials there said, potentially becoming the first country to take such a step as concerns about the threat the virus poses to people intensify.

The vaccine campaign will be limited, with doses set to be available to groups including poultry farmers, veterinarians, scientists who study the virus, and people who work on fur farms housing animals like mink and fox and where there have been outbreaks.

In an email, Mia Kontio, a health security official at the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, told STAT the country was waiting for 20,000 doses to arrive, but planned to administer them “as soon as the vaccines are in the country.”

The decision to start providing vaccines reflects fears that people in close contact with infected animals could contract the H5N1 virus themselves. The virus is, for now, not particularly adept at infecting humans or, more importantly, spreading among them. But scientists worry that as the virus infects more mammalian species, and if it encounters more human cells, then the higher the chances are that it evolves to become more of a threat to people.

The Finnish campaign also comes as the U.S. faces an H5N1 outbreak among dairy cattle — previously a species scientists thought wasn’t susceptible to the virus. Three dairy workers have had confirmed infections tied to the outbreak, and although the infections were all mild and there were no signs of forward transmission to other people, the cases underscored the risk to people who have contact with infected animals.

“The concern here is about the animal-human interface,” said Marc Lacey, the global executive director for pandemic at CSL Seqirus, the maker of several H5 vaccines, including the one Finland is planning on using.

Other countries are discussing deploying H5 vaccines or are working to secure supplies, Lacey said. The U.S., for example, last week hired CSL Seqirus to build up the number of H5 flu vaccine doses it has available. But Finland was the first country he knew of that actually planned to use the vaccine, at least in recent years outside research studies.

The vaccine to be administered in Finland is designed off a different avian influenza virus called H5N8, but researchers say the shot should still confer protection against H5N1. It’s the hemagglutinin component of the vaccine — the H part — that’s the main target. The vaccine also includes an adjuvant, a component that deepens the generated immune response.

European regulators authorized the vaccine, which is known as Zoonotic influenza vaccine Seqirus, based on a number of studies showing that it elicited immune responses that scientists think would be protective against avian influenza. Researchers can’t run traditional efficacy trials with such products because the virus isn’t circulating among people, so they’re typically approved based on these immunogenicity studies. The immunization is approved as a two-dose vaccine, with doses given at least three weeks apart.

Isabella Eckerle, a virologist at the Geneva Centre for Emerging Viral Diseases, said that vaccinating people at high risk of exposure to the virus could protect them, but she said the world should not rely on human vaccination to prevent the H5N1 situation from worsening. Instead, health officials should work to limit transmission broadly, including among animals. Such efforts could include improving the use of personal protective equipment, or PPE, on farms, she said.

(In the U.S., health officials have made PPE available to dairy farms, but few have taken them up on the offer. Milking parlors can be hot and humid, meaning it’s not particularly pleasant to wear goggles, gowns, and masks.)

“The most important thing would be not to have this virus circulating,” particularly in mammals, Eckerle said.

She added that other flu vaccines can’t always halt transmission, even if they reduce the risk of serious illness. It’s possible then these vaccines will perform similarly.

“They might prevent symptoms or disease, but we don’t know if they prevent infection,” she said.

Scientists have worried H5N1 could pose a pandemic threat since its discovery nearly 30 years ago. But in just the past few years, the virus has expanded its global footprint and its list of victims, spreading to just about every corner of the world and sickening and killing scores of wild and domesticated birds. It’s also found its way to an increasing number of mammals. The dairy cow outbreak — which thus far has only been seen in the U.S. — is the latest twist in its history.

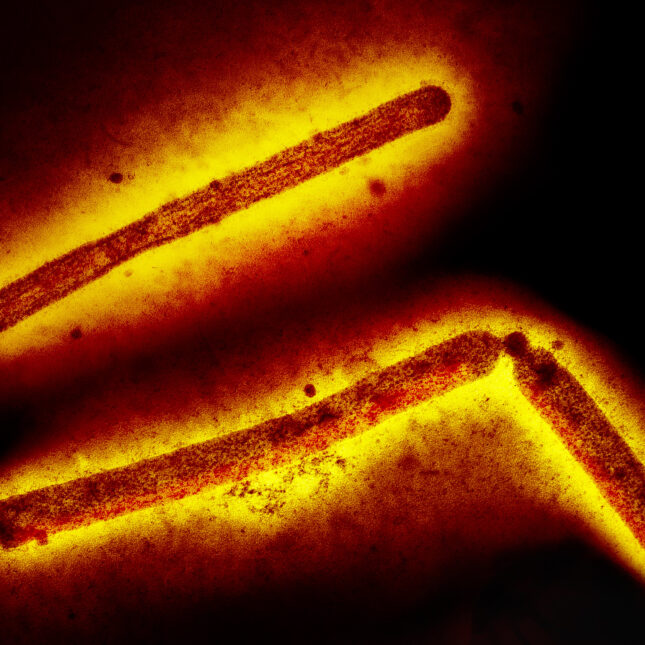

Finland, in particular, has been dealing with H5N1 outbreaks not just among birds, but on its fur farms, with at least 71 farms having cases last year. While most of the farms housed foxes, it’s the spread of the virus in mink in particular that heightens concerns. The receptors the virus uses to infiltrate their cells are thought to be similar to ours, possibly providing the virus with a training ground to become better at infecting our cells. Moreover, mink can be infected by avian and human flu viruses simultaneously, which could allow the viruses to swap genes and for the resulting pathogen to become more adept at spreading among people.

Last month, Finnish authorities announced expanded surveillance measures for the virus on the country’s fur farms; those measures will be in place through the end of September, a stretch when officials said the risk of transmission to the farm animals from wild birds was at its highest. But officials noted that Europe has documented fewer infections in wild bird populations this year than have been seen in the recent past.

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.

STAT encourages you to share your voice. We welcome your commentary, criticism, and expertise on our subscriber-only platform, STAT+ Connect